In the last post we built a savings foundation, your cushion. Once that cushion feels real (think: your essentials are covered for a while and surprise bills don’t ruin your sleep), the next step is to put those dollars to work. That step is investing. There are several ways to invest (or gamble in the markets), but we will explore it using the KISS principle (Keep it simple stupid!).

Think of investing as a machine you build, quiet, sturdy, and designed to run for years. You don’t need to tinker with it every day. You need to assemble it well, feed it regularly, and avoid yanking the levers when headlines get loud. When it’s set up right, it keeps compounding in the background while you live your life.

This machine runs on three things:

- Discipline: Show up on a schedule. Contribute every payday. Ignore hot takes.

- Patience: Give time a chance to work. Compounding pays the most to the investor who can wait without fussing.

- A thoughtful plan (the one you can stick to): Simple beats fancy. If you can’t follow it in a rough market, it isn’t your plan.

This isn’t about predicting the next winner or day-trading your way to glory. It’s about building a process that outlasts your emotions and outpaces inflation, so your money protects your future options, yours and your family’s.

From here, we’ll cover why investing matters, the basic building blocks, the paths you can choose, and a simple starter setup you can turn on today. Let’s do this!

Why Investing Matters

Outrun inflation.

Prices creep up over time. If your cash just sits still, it quietly buys less each year. Investing is how you keep (and ideally grow) your purchasing power, so tomorrow’s dollars still do real work for you.

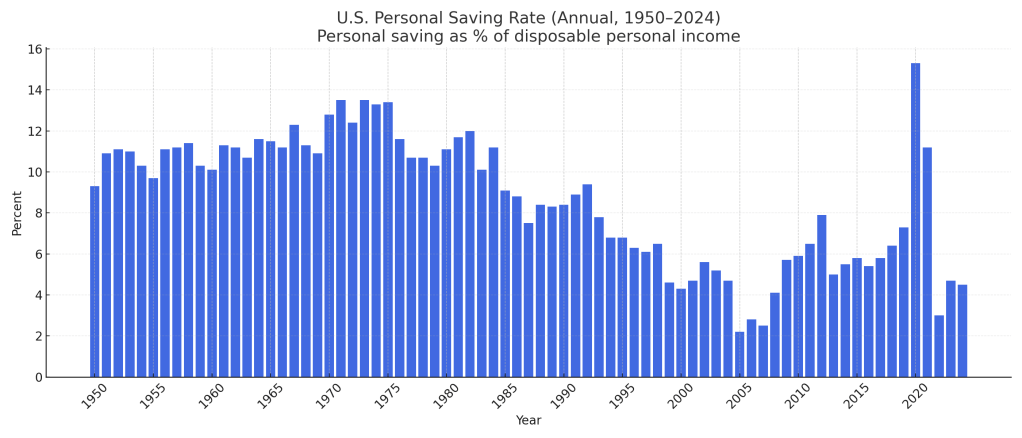

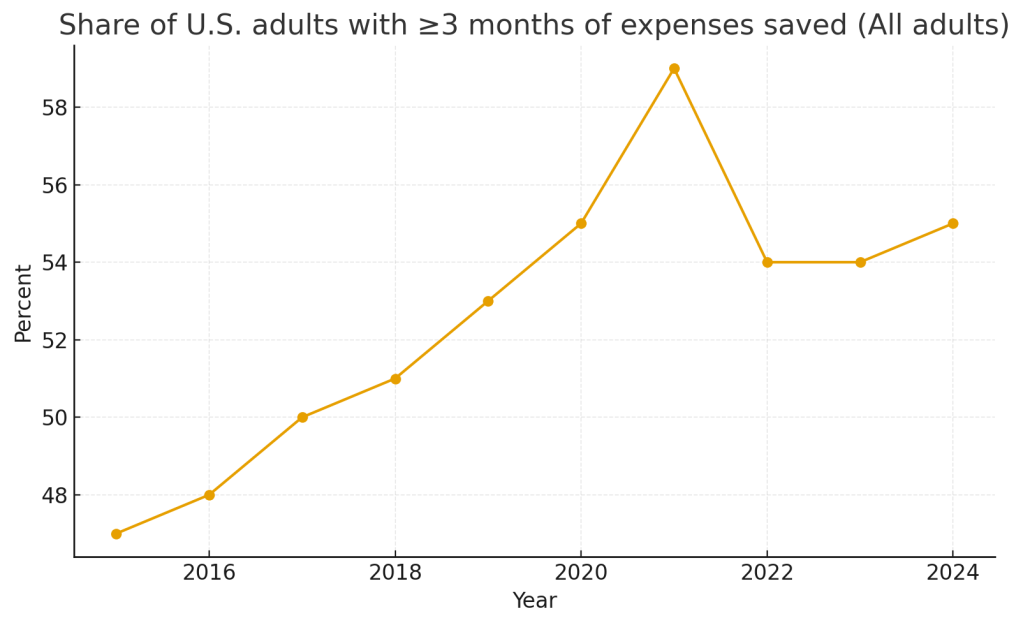

Let’s take a look at how inflation rates have behaved during the last 50 years in the US:

Inflation rates subsided starting in the 1980’s and all the way through the 2000’s. After COVID it started to show its ugly head again. And even though it is now in the 2-3% range, it serves as a reminder that we can’t take low inflation as a given.

Let compounding do the heavy lifting.

Compounding is money earning returns on its past returns, growth that feeds on itself. Early on it feels boring… then it bends upward.

This classic story demonstrates the concept: a courtier asks a king for payment in rice, one grain on the first chessboard square, then double on each next square. Sounds modest. But by the halfway point (square 32), you’re already in billions of grains. By the end (square 64), the total is about 18 quintillion grains, so much rice that no kingdom could deliver it. That’s the nature of exponential growth, it looks slow, then suddenly impossible to ignore.

Investing works the same way. In the early years, progress feels small; later, the curve does the work if you keep adding and don’t interrupt it. A simple example: set $10,000 in motion and add to it regularly; at ~7% a year, it roughly doubles about every 10 years (Rule of 72). The big gains arrive late, rewarding the person who started and stayed the course.

“The first rule of compounding: never interrupt it unnecessarily.” — Charlie Munger

The Building Blocks

Let’s talk about the basic building blocks you can use, nothing fancy, just the pieces that make a solid portfolio without drama.

Note for later posts: There’s a wider menu, real estate, private equity, private credit, venture capital, commodities, and more. They can add diversification/return for some investors, but come with access, liquidity, and fee tradeoffs. We’ll cover them separately. For now, keep it simple and master these basics.

Cash & cash-like (T-bills, high-yield savings, money market funds)

- What it is: Dollars you can tap soon with minimal risk.

- Why it matters: Stability for short-term goals and emergencies; helps you sleep at night.

- Tradeoff: Lowest expected return; great parking spot, not a growth engine.

Bonds (fixed income)

- What it is: Loans to governments or companies; you earn interest and prices move with rates.

- Why it matters: reduces portfolio swings and provides income so you stay invested.

- Main risks: Rate risk (prices fall when rates rise) and credit risk (issuer can’t pay).

Stocks (equities)

- What it is: Ownership in actual real businesses (something that many investors forget); returns come from profits growing over time.

- Why it matters: The engine of long-term growth and compounding.

- Tradeoff: Bumpier ride, volatility is normal and the price of admission.

Funds & ETFs (your diversification shortcut)

- What they are: Baskets of many stocks/bonds in one ticker, instant diversification.

- Index vs. active: Index funds track (or parts of) the market at very low-cost; active funds try to beat it (sometimes do, often don’t, and fees bite).

- Costs matter: Expense ratios are silent performance killers—keep core funds low-cost (ideally ≤0.2%).

Considerations & Basic Questions to Ask Yourself

1) What are my financial goals? Goals decide the strategy. Retirement, college education, home downpayment, or just wealth creation

2) What is my risk tolerance? Dictates your asset allocation. If you can tolerate a temporary 30% drop without panicking, you can consider tilting your portfolio towards stocks.

3) What is my investment goal (time horizon)? Time determines how much volatility you can ride.

4) Do I have a clear understanding of the investment? Fees, risk, and liquidity drive outcomes.

5) Do I need an investment professional? Planning + behavior coaching can be worth it, especially if you have a more complex financial situation. Alternative, go DIY with a simple index plan, which most starting investors should follow.

6) How much can I afford to invest? Avoid forced selling and let it compound in time. Assumes you have a 3–6 months of expenses saved and no high-interest debt outstanding.

7) Is the investment income taxable? Taxes affect net return. Which type of account are you focusing on? (Taxable account, HSA, 401K, IRA).

8) How is the investment performing compared to others? Compare your stock and bond portions to the appropriate benchmarks once or twice a year, then rebalance; don’t chase last year’s winner.

9) Are my investments diversified enough? Reduces the chance one mistake wrecks your plan.

Diversification — The Only Free Lunch in Finance

I purposely ended the previous section with the Diversification question so we can dive deeper now.

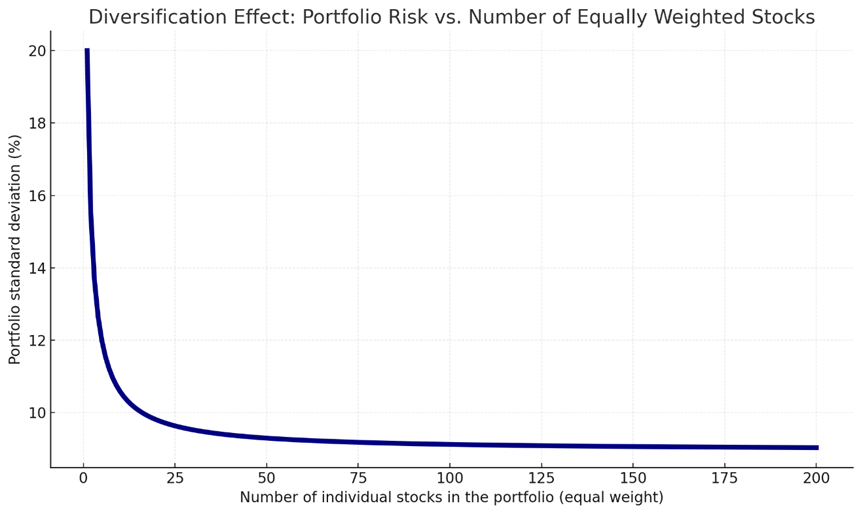

Diversification spreads your bets so no single security or sector can sink the plan. Add more independent (or less-correlated) positions and you shave off unsystematic risk (company-specific stuff). while the systemic (or market) risk remains. That’s the “free lunch”, for the same expected return, you can usually get less volatility just by broadening your holdings.

BUT… also keep in mind that you can add lots of overlapping funds and you get “diworsefication”, basically more line items but not true diversification. Five S&P 500 funds is still the S&P 500; three tech ETFs that all hold the same ten names won’t protect you when tech wobbles (and this happens more than you think, especially in today’s large tech dominance environment). The fix is simple, own broad markets at low-cost, and keep your core small (2–3 index funds) so you rebalance and stick with it.

The illustrative chart below shows a classic effect, as you increase the number of equally weighted stocks in a portfolio, total volatility drops quickly at first, then plateaus. Why the plateau? Because stocks tend to move together (correlation), so some risk can’t be diversified away. The first 10–30 names do most of the work. After that, the benefit diminishes unless you diversify by region, sector, and asset class (e.g., add international stocks and high-quality bonds).

An approach to get started – Beginner Level

Here is a basic way to establish a starter low maintenance portfolio. Just a quick guide to get your feet wet.

- Pick ONE portfolio you can live with:

One-fund autopilot

A target-date index (or “balanced index” if no target-date) that auto-diversifies and rebalances.

Two-fund global

- Total World Stock Index (or US Total Stock + International Total Stock).

- Total Bond Market Index.

Three-fund classic

- US Total Stock (50–60%).

- International Total Stock (20–30%).

- Total Bond Market (20–30%).

2. Set your allocation or mix based on time horizon (ballpark, adjust to sleep-at-night level):

- 10+ yrs: ~80/20 stocks/bonds.

- 5–10 yrs: ~60/40.

- <5 yrs: this is savings territory (cash/T-bills/short bonds).

3. Automate & maintain

- Contribute every payday. Add an auto-escalator (+1%/quarter or after raises).

- Rebalance 1–2×/yr (or let the target-date fund do it).

- Turn off trading prompts/alerts that tempt tinkering.

- Write a 1-page plan: goals, funds, target %, contribution amount, rebalance rule.

- Use a 24-hour rule before any portfolio change.

When (and How) to Use an Advisor

Fundamentally, you don’t need an advisor to invest well. But the right one can add real value, especially if your situation is complex or your behavior gets in the way.

When it’s worth talking to one:

- Complexity triggers: equity compensation from work (RSUs, ISOs, concentrated employer stock, multiple old 401(k)s), small business sale, inheritance, tricky taxes, college/retirement modeling.

- Behavior triggers: markets keep you up at night, you procrastinate, or you bail in selloffs.

- Time triggers: you’ll do nothing unless someone owns the process with you.

- Marriage/Partner dynamics: You may be the one that “manages the home finances”, while your partner is more hands-off. You may want to have somebody ready that he/she can rely on if you are not available.

What “good” looks like

- Fiduciary, fee-only. They must put your interest first and not be paid by product sales.

- Evidence-based, low-cost portfolios. Index core, broad diversification, simple rebalancing rules.

- Planning-first. Investments support a written plan (not the other way around).

The value test (use this before hiring)

Will the advisor’s planning + tax help + behavior coaching likely exceed the fee drag over time?

If yes, then proceed. If not, then DIY or an advice-only session.

Conclusion — Keep Building the Machine

You can do this.

If your savings are the cushion, investing is the machine you’re building on top of it, quiet, sturdy, patient. It doesn’t need to be clever; it needs to be consistent. Set your rules, follow your map, and give compounding time to work.

Stay disciplined:

- Keep contributions automatic.

- Keep costs low and the portfolio diversified.

- Rebalance by rule, not by mood.

- Use your one-page plan when headlines get loud.

Avoid the noise and the get-rich-quick detours. Most “secret strategies” are just fees in disguise or risk with a new label. Your edge isn’t prediction, it’s behavior. Show up each payday, let the boring parts do their job, and protect the system from your own impulses.

Your portfolio is a reflection of choices repeated over years, not a single brilliant trade. Keep adding steady inputs, keep friction (fees, taxes, tinkering) low, and the output compounds, slowly at first, then meaningfully.

If you stick to your map, the math quietly stacks in your favor. Future-you, the one with options, time, and calm, will look back and be grateful you chose boring over flashy, process over prediction, patience over panic.