Several times a year, usually when talking about world events that feel like they might change our lives in some way (and lately, those seem to be happening more often), I catch myself giving the same almost automatic response: “we better save our money.”

Some people look at me strangely, others nod in agreement, or at least I think they do.

The reason I keep saying it is simple: I believe savings give you flexibility, freedom, mental peace, and room for error. As the world gets more unpredictable, you want more capacity to absorb mistakes and shocks, without risking ending up on the street.

Some will say that this is a pessimistic view, and guess what…they’re right. But it’s also realistic. Life throws curveballs. A job loss, a health scare, a market downturn, these things don’t send a calendar invite before arriving. Having savings is like carrying an umbrella, maybe the sky looks sunny today but when the rain comes, you’ll be glad you packed it.

But here’s the part that gets overlooked, savings aren’t just about defense. They’re also about offense. Having money set aside means you can take advantage of opportunities when they show up. Maybe it’s joining a project you feel passionate about, investing in something you believe in, or even taking time off to pursue a personal goal. Being prepared gives you the freedom to say yes when others can’t. And that’s the optimistic side of saving. It’s not just about minimizing risk; it’s about maximizing possibility. It’s the foundation that lets you build, experiment, and pursue what matters without being paralyzed by “what ifs.”

But here is the thing, if saving is so powerful, why do so many of us struggle with it? Why is it so much easier to hit “buy now” than to move money into a savings account?

I want to be clear here: when I say the word savings, I really mean savings + investing. After all, having idle money sitting in the bank is far from ideal. But for the purposes of this post, we’re going to concentrate only on the savings portion, the habit, the psychology, the discipline. We’ll leave the investing side for another occasion.

Now…going back to why it’s so hard to save. If you think about it, we’ve always been immersed in an environment that pushes us to spend, and to do it constantly. Companies spend immensely on marketing and advertising for a reason: because it works. And if you think you’re immune to these tactics, think again. Nobody is totally immune.

And when you add convenience and speed on top of that (same-day shipping, one-click checkout, subscriptions that auto-renew), extra spending becomes almost effortless. The path of least resistance is almost always toward consumption, not saving.

The Psychology of Saving

This naturally leads us into a bigger issue: instant gratification.

Every time you buy something, scroll a feed, or click on a notification, your brain rewards you with a tiny hit of dopamine. It’s the same brain chemical that fires when you achieve a goal, eat good food, or receive a compliment. Dopamine is powerful, it’s designed to reinforce behaviors that lead to rewards.

The tricky part is that in our modern hyperconnected, short-attention-span lives, we’re always chasing that next dopamine hit. It may sound harsh, but the reality is that technology, with all its benefits, also has made us addicted to this mechanism. What was once a system meant to reward natural human actions (hunting, working, bonding with others), has been hijacked and it is losing its purpose.

And “action” is the keyword here. Dopamine fires when we do something. In the past, that action might have been planting seeds or creating something meaningful. Today? It might just be “watch another video” or “buy another pair of shoes.”

This is why saving feels a bit unnatural. Moving money into a savings account doesn’t trigger the same rush. There’s no flashy marketing campaign cheering you on, no instant confirmation email, no package arriving at your door. In fact, it feels like the opposite, you’re giving something up today without getting anything back right away.

Discounting the future

Psychologists call this present bias, the tendency to value immediate rewards more than future ones, even when the future rewards are much larger. For example, many of us would prefer $20 today over $25 in a month, even though waiting just a little longer would give us more. The future feels distant, uncertain, and less exciting. We have all heard about the marshmallow experiment and the ability to wait for a larger reward, but hey, if you won the lottery today, would you want a lump sum and receive a fraction of the jackpot or get the deferred annual payments for the full payout? (I know there are other factors to that decision, but you get my point).

When you combine present bias with the dopamine loop fueled by technology and marketing, it’s no wonder saving is difficult. We’re swimming against powerful evolutionary and societal currents every time we choose not to spend.

The social dimension: everyone else is doing it

On top of biology, there’s culture. Social media constantly showcase lifestyles of consumption, travel, fashion, gadgets, experiences. Comparison pressure makes spending not just easy but almost expected and justified. Saving, on the other hand, is invisible. Nobody posts, “Just put $500 into my emergency fund, feeling cute, might save again later.”

So why bother?

Because this is where saving reveals its hidden strength. Unlike the fleeting dopamine rush of spending, it doesn’t feel good immediately, but the payoff compounds over time. Each act of saving is an act of resistance and defiance; you are choosing your future self over your present self.

And while spending offers instant gratification, saving builds something deeper: delayed gratification. The ability to do this isn’t just a financial skill, it’s a life skill. People who can wait, resist, and invest in the future tend to have better outcomes across health, relationships, and career.

In other words, saving isn’t just about money. It’s about training your brain to operate differently in a world wired for distraction and consumption. You’re rewiring yourself for patience, resilience, and long-term thinking.

Training the Muscle

Think of saving like going exercising or training. Nobody walks on day one and lifts 200 pounds or starts running a marathon. You start small, with manageable reps, time or distance and gradually build from there. Would you judge or make fun of someone that is out shape for showing up every day in the gym? Of course not! That person deserves daily applause! The same is true with money.

When you first start your career, the amounts you’re able to save might be small, and that’s perfectly fine. What matters more in the beginning isn’t how much you save, but that you save. Each contribution, no matter how small, is a rep. It’s training the muscle.

Habits first, amounts later

At the start, saving $20 or $50 a month may not feel life-changing, but it builds something even more valuable than the money itself: habit and discipline. Once saving becomes automatic, you don’t have to fight the same internal battle every time you get paid. It’s just part of your system, like brushing your teeth or grabbing your morning coffee (but not the expensive one!).

Over time, those small amounts begin to add up. But here’s the real magic, you’re not just compounding money. You’re compounding behaviors. With each repetition, you’re strengthening:

- Discipline – the ability to stick to a decision even when temptation calls.

- Systems – creating routines and structures that simplify life decisions.

- Willpower – developing confidence in your ability to prioritize long-term rewards over short-term desires.

The “good” dopamine hit

Now here is a twist, saving eventually gives you dopamine too. The first time you check your account and see that your emergency fund crossed certain amount, or you hit a savings milestone you didn’t think was possible, that’s a dopamine hit. But unlike the fleeting buzz from buying something new, this one last longer. It’s tied to progress, achievement, and security.

Over time, this feedback loop turns saving from a chore into a source of pride. Just like a gym-goer who starts craving the post-workout endorphin rush, savers begin to crave the sense of control and growth that comes with watching their balance climb.

The Data — How America Saves

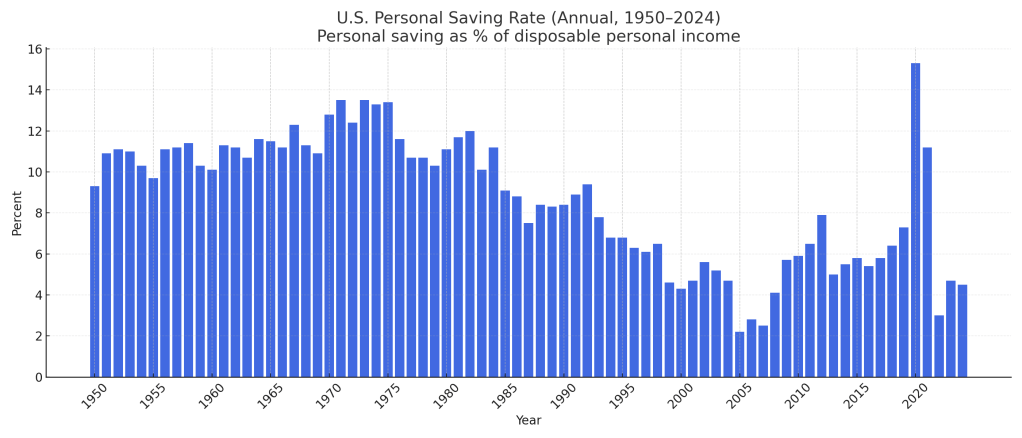

Let’s put some aggregate numbers into all this. The U.S. tracks how much people save as a share of disposable income (the personal saving rate) which gives a clear window into saving behavior through time.

From the 1950s through the mid-1980s, the saving rate generally hovered around the 10–12% neighborhood. Then came a long downtrend, with the mid-2000s marking the low point: on an annual basis, 2005 was about 2.2%. After the Great Financial Crisis, the rate drifted back to the mid-single digits (roughly 5–7%) through much of the 2010s, well below previous averages.

One eye-popping outlier is 2020–2021, clearly the pandemic years. Annual readings printed 15.3% (2020) and 11.2% (2021). Two forces drove this temporary jump:

- Incomes jumped from government transfers (stimulus), lifting disposable income, and

- Spending collapsed during lockdowns (fewer outlets to consume).

As the economy reopened and transfers faded, savings normalized back toward pre-COVID levels. That’s still notably below the mid-century average, which suggests that, for many households, saving often shows up as an afterthought rather than a default.

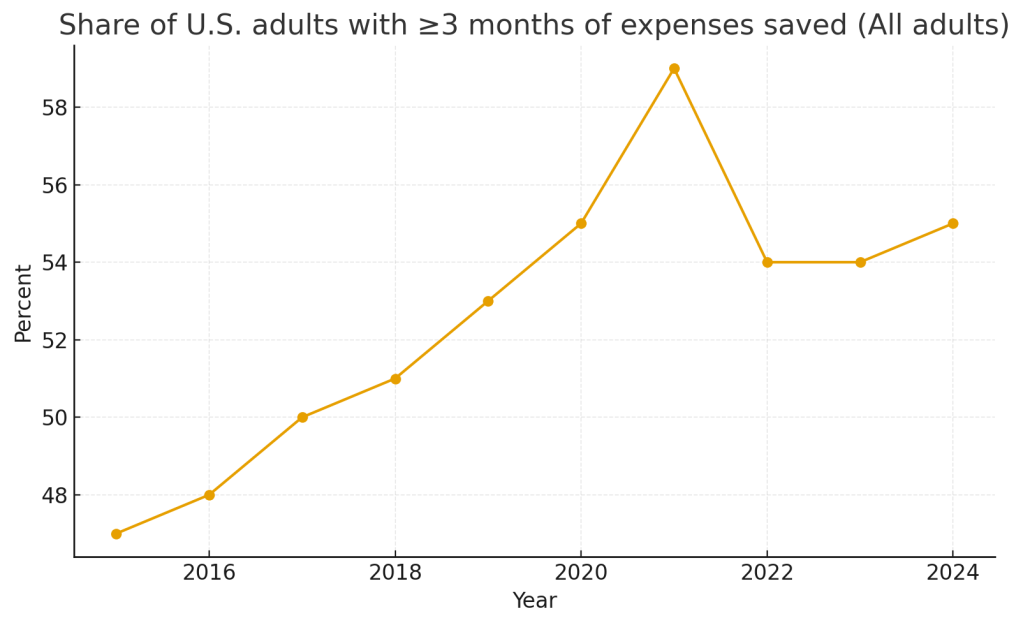

That’s one lens. Now let’s look through another: the Fed’s SHED survey, which asks whether people have an emergency fund of at least three months of expenses.

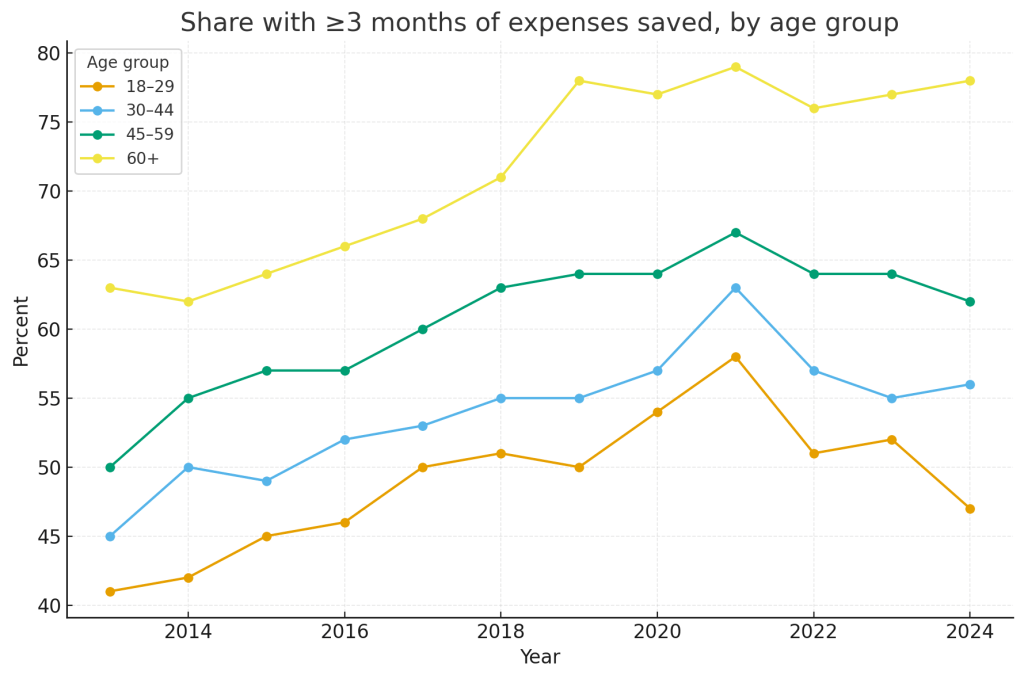

At first glance, the picture looks a bit better. A little more than half of U.S. adults report having ≥3 months saved. Over the last decade this share has edged higher (again, with a pandemic-era spike and then a return to the mid-50s). When you split it by age, the pattern holds, but you also see that younger folks are less likely to have that cushion than older adults, which is expected and even reasonable given life stage (older households are near or in retirement).

But perspective matters. Emergency funds adequacy depends on your situation: income stability, how long it might take you to replace a job, whether you have dependents, and whether you have backstops (credit, family support, liquid investments you’d tap).

So don’t get me wrong, having roughly half the population at this minimum level is decent progress. But it still leaves the other half of households more vulnerable to shocks and surprises. Additionally, if we raise the bar to say…six months, that share would likely drop meaningfully.

How to Start Saving Today (Practical Tips)

I’ll assume you’re at an early stage with savings. From that starting point, the goal is to start small and build habits, discipline, systems—and, yes, dollars.

1) Make it easy

- Automate it. Set a recurring transfer on payday to a separate, high-yield savings account. Out of sight = out of mind.

- Name the bucket. “Future Me Fund,” “Buffer,” “Freedom.” Labels make it real.

- Kill friction points. Turn off one-click checkout, remove cards in browsers, unsubscribe from impulse-trigger emails.

2) Start small (and make it attainable)

- Pick a number you can hit without white-knuckling, $20/week, 1% of pay, etc.

- Use an auto-escalator: bump contributions +1% every quarter or after each raise.

- Treat each transfer like a rep, we’re training the muscle.

3) Run the “fast vs. durable joy” test before spending

- Ask: Will this give me a quick, volatile dopamine pop, or lasting satisfaction?

- If it’s “fast and volatile,” insert a 24-hour pause. If it’s “durable,” spend with intention.

- Is not about “never spend”, it’s about being conscious and values-aligned with each dollar.

4) Track progress & milestones

- Keep a simple scoreboard (note or app). Celebrate thresholds:

- First $500 → micro-emergency buffer

- $1,000 → basic peace of mind

- 3–6 months of expenses → robust cushion

- After you hit your emergency target, route incremental contributions to your future investing bucket.

5) Celebrate wins (yes, even with the expensive coffee)

- Each milestone earns a small, deliberate reward. The good kind of dopamine.

- Reflect on the flexibility you’ve gained: fewer money anxieties, more choice.

- Then get back to your reps.

Conclusion: Reps Build Freedom

If there’s one thread running through this whole piece, it’s that saving isn’t just cash in an account. It’s a practice that buys you flexibility, freedom, room for error, and the ability to say yes when a real opportunity shows up. It’s defense and offense.

We also must be honest about the world we’re in, our brains crave the quick dopamine hit, and modern life is engineered to sell it to us fast, easy, one click away. Recognizing that pull isn’t cynicism; it’s awareness. You don’t need to impress anyone with spending. Impress yourself with results.

So, we train the muscle:

- Start small and make it easy (automate it).

- Build habits, discipline, and systems that carry you when motivation dips.

- Use the fast vs. durable joy test before spending.

- Track milestones and celebrate progress.

- Let the good kind of dopamine come from seeing your cushion grow.

Do this long enough and you don’t just build savings, you build a steadier, more resilient version of yourself. That’s the real win.

If I can leave you with anything from this post, it’s the same phrase that started it: “we need to save our money.”

Leave a comment